Diagnosis: Coats’ Disease

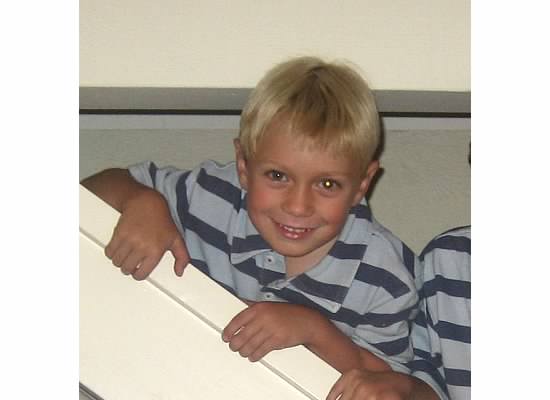

Uploading family photos is something we all do – posting and sharing across our social platforms or saving to our phones for easy access. This is especially true for parents of young children, capturing milestone moments of those first years of life. Normally, we don’t give this simple act a second thought — but for me, taking and sharing digital photos of my then five-year-old son, Benjamin, changed the entire course of our family’s life. Simply put, those pictures literally saved Ben’s life – and his sight. Our story is a cautionary and valuable tale for all parents of young children to learn from, and act differently when it comes to their child’s eye health. In sharing our story, my hope is for every parent to look at their family photos through a new lens, know how to look for The Glow, and start early with periodic eye checks with an eye specialist.

When I was looking back at family photos, I noticed my son Benjamin had a recurring golden flash in his left eye. I didn’t think too much about it, guessing the mysterious glow could be from the camera angle, the little freckle in his left eye he was born with, the flash or dim light, or just poor photo quality. Besides, Benjamin had been getting annual health check-ups with his pediatrician since he was born and everything seemed fine. I shrugged it off.

Then, my sister called to tell me about a TV show she’d seen that warned about the dangers of “cat’s eye reflection.” Turned out, she had noticed a similar glow in Benjamin’s left eye from photos she’d taken during a family trip.

I got that sinking feeling and sprung into action, immediately digging through the internet, afraid of what I’d find. When every Google search result lead me to retinoblastoma, a rare cancer of the eye, I took Benjamin to the pediatrician for an eye exam right away.

What I didn’t know then was that this gold flash, invisible to the naked eye, could indicate at least 20 different eye diseases or conditions. Benjamin’s vision was rapidly deteriorating right in front of my own eyes, and I didn’t see it.

During this visit with our pediatrician, Benjamin received a “paddle” eye test, where he read out loud the letters on a vision chart while the doctor covered his left eye with a paddle.

The pediatrician didn’t immediately see anything wrong, as Benjamin passed this test and had done so before; but because of the photos I showed him of Benjamin’s glowing eye, he performed a red reflex exam. That’s when he noticed that something was wrong, and he referred us to the head of Pediatric Ophthalmology at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, requesting that his appointment be within five days.

Not wasting time, I called for an appointment with the ophthalmologist and managed to get Ben seen by him the very next day. Here, the ophthalmologist gave Benjamin an Optical Coherence Tomography scan, which showed a large white mass in the pupil behind the lens of his left eye—the culprit of the visible glow in our photos.

We were stunned. Benjamin was legally blind in his left eye, but hadn’t exhibited any of the typical signs of blindness, like bumping into walls or rubbing his eyes.

The ophthalmologist guessed Benjamin had passed the “paddle” eye test in the pediatrician’s office during his annual health check-ups by moving the paddle just enough to let his unaffected eye take the test. But when the ophthalmologist taped up and “sealed” Benjamin’s right eye, his left eye could not see the biggest letter E, just eight feet away. The “paddle” eye test isn’t foolproof, or kid-proof in this case.

It turns out, our experience is quite common. Pediatricians often miss The Glow, medically known as leukocoria, which is an abnormal reflection from the retina of the eye and can indicate at least 20 different eye diseases and conditions.

In fact, because The Glow often appears as a white, opaque, or yellow spot in the pupil of the eye in photos taken with flash, parents are far more likely to identify The Glow than their pediatricians – almost 80 percent of the time. We also know that one in 80 children may show The Glow in the first five years of their lives. Each is at risk for a serious eye disease and possible blindness, just like Benjamin.

We were immediately sent to The Vision Center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles for further testing. Here, Benjamin received an official diagnosis for Coats’ Disease , a rare and progressive condition that causes partial or complete detachment of the retina, eventually leading to complete loss of vision in the affected eye.

Like 80 percent of other glow-related eye diseases, loss of vision can be prevented with early treatment. He soon began a series of three laser eye surgeries, all complete before his seventh birthday. While we expect Benjamin will undergo additional eye surgeries later in life, and his vision is most likely permanently gone in his left eye, we feel fortunate all the same; we caught the disease early enough to save at least some of his vision in his left eye.

Today, Benjamin is a happy, resilient teenager who loves to play sports, especially wrestling, football and lacrosse.

Once our family overcame the immediate crisis and we settled back into daily life, I couldn’t stop thinking about The Glow. As I learned more, I felt an obligation to tell other parents about this life and sight-saving tool.

Who knew a glow in the eye, easily captured in flash photography, could be so dangerous?

Why don’t most children receive a comprehensive eye exam until they enter grade school—far too late to catch treatable and preventable eye diseases like Coats’— especially since one in 80 children will present with The Glow at some point before the age of five?

What if Benjamin had lost his sight in both eyes— or worse, lost his life because I just wasn’t aware of the signs?

No child should lose their sight needlessly. I didn’t want another mother to carry that kind of guilt, simply by not acting sooner because she didn’t know.

So with the help of my two best friends, Sandra Roderick and Lannette Turricchi, we launched Know the Glow, a national campaign to communicate this simple message to parents:

- Check your photos or take new photos of your child.

- Because The Glow may not always show up, review or look back at family photos, especially where your child is looking at the camera.

- Make sure to take or use photos where the flash is turned on and the red eye reduction featured is turned off.

- Look for The Glow, a white, opaque, or yellow spot in the pupil of one or both eyes. If you see The Glow once, be alert, but if you see it twice in the same eye, be active.

- Ask an eye specialist—an optometrist or ophthalmologist—for a comprehensive eye exam, including a red reflex test. If you do have photos of your child showing The Glow, bring them with you to your appointment.

- Help us spread the word, especially to parents of young children [ages 0-5], about the importance of comprehensive eye exams including the red reflex test.

Because no child should go blind from a preventable eye disease.